In December

1811, London was horrified by two murderous attacks on families in Wapping

district within twelve days, claiming seven lives. Wapping was then a major

port area full of docks and warehouses, businesses catering to the seafaring

trade and sailors, full of low taverns, and brothels. It was a derelict and

often violent neighbourhood, but it had never experienced anything like what

happened in 1811.

The first

attack took place on December 7, at 29 Ratcliffe Highway (now known as The

Highway). The victims were three members of the Marr family and an apprentice who lived in a flat behind the Marr's linen draper’s shop.

At sometime around

midnight, an intruder entered the home and brutally bludgeoned to death Timothy

Marr, his wife Celia, their four weeks old son, and the apprentice, James Gowan.

A blood-stained maul (pictured below) found on the premises with the initials JP or IP was assumed

to be the murder weapon. The Thames River Police investigated but could

discover neither motive nor suspects.

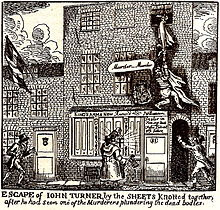

On December

19, a second murderous attack took place nearby at the King’s Arms, a tavern at

81 New Gravel Lane (now Garnet Street). After a constable had heard cries of “Murder!”

a crowd gathered at the premises, where they found a lodger, John Turner, descending

from an upper floor using a rope of knotted sheets.

Turner was crying and nearly

incoherent. Inside, the crowd discovered the bodies of the owner, John

Williamson, his wife Elizabeth, and a servant, Bridget Harrington. Their skulls

were crushed and throats cut. In a bedroom upstairs, they found the Williamson’s

fourteen-year-old granddaughter fast asleep. Amazingly, she had heard nothing.

Bow Street Runners and constables from other districts joined the investigation after the

second attack. (London did not have a centralized, professional police force until 1829). The press and a panicked public were clamouring for a quick arrest

of the killer(s). Within a few days, the police arrested three men as suspects.

One of them, a sailor named John Williams (or Murphy) was a lodger at a Wapping

public house, The Pear Tree. (Image: John Williams, post-mortem sketch).

On December

24, the investigators learned from another lodger that the maul found at Marr’s

shop belonged to a third lodger, John Peterson, who was at sea, and that

Williams could easily have had access to it. Other discoveries led them to focus on

him. Four days later, Williams hanged himself in his cell. The courts quickly ruled him the murderer. But curiously, he did not fit Turner’s description of the man he had seen in the King's Arms. Williams was slender in build and of medium height. All the evidence against him was

circumstantial.

Home

Secretary Richard Ryder, elated by the “solution” of the case, ordered William’s

body to be publicly paraded through the streets of Wapping, and buried at the

crossroads of New Road (now Commercial Road) and Cannon Street Road. The aim

was to reassure the public that the murderer was indeed dead. On New Year’s Eve,

the body was removed from the prison on a cart and followed by a huge procession

estimated to be around 180,000 persons. The procession was the subject of many contemporary images.

The marchers stopped before the houses of the victims before proceeding to the intersection named. A stake was driven through William's heart and he was placed in an already dug

grave. At the time, suicides could not be buried in consecrated (church) ground

and the stake was supposed to prevent his soul from wandering.

Debate continues

today about whether Williams was indeed the killer, or merely the unfortunate

scapegoat of authorities eager to appease the public clamor and panic. Other

suspects have been considered, but the true identity of the Ratcliffe Highway

Murderer remains a mystery, much like the identity of the Whitechapel Murderer, Jack the Ripper.

Further Reading:

T.A. Critchley and P. D. James, The Maul

and the Pear Tree: The Ratcliffe Highway Murders, 1811. London, 1971.